Before I spend any time getting into my visit to Fort Monroe and meeting with Cindi, I think it would be helpful to give a little context and history of the fort itself. Have you ever wondered how it came to pass that the United States spends 17 times as much on national defense than the next 10 countries combined? A good place to begin to answer that question is with the defensive forts built along the eastern shore. Of which Fortress Monroe is one.

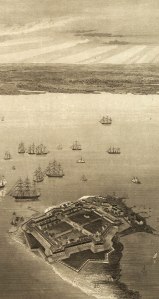

After the American Revolutionary War a handful of forts were built around the country in strategic locations, like West Point, to defend or repulse specific areas from attack. Then the war of 1812 saw the United States invaded and it’s capitol destroyed. From then on the U.S. took the military establishment to a whole new level and built a series of what ultimately became 42 forts. Fort Monroe, begun in 1819 and completed in 1834, is a Third System fort. The First System being British forts taken during the Revolution. The Second System being those forts constructed after the Revolution. Shaped as a six sided polygon with pointed corners Fortress Monroe is built of brick and stone and is surrounded by a moat. It is the largest fort built in the United States. It was designed by Simon Bernard, a French General of Engineers. Why hire out a Frenchman to build American defenses? Because the US had no school of engineers at the time, thus no engineers to design forts.

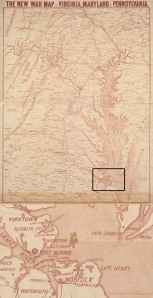

Since no other country occupied the lower portion of the North American continent in 1800, save The United States, all her potential threats were on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. When planning its defense it was only necessary to be concerned with a naval invasion. In the process of reconstruction after 1812 President James Madison created a commission to plan and build a network of coastal defenses up and down the eastern seaboard. You can see from the map above what a major thoroughfare the Chesapeake Bay is. From it’s mouth one can get from the Atlantic Ocean to the heart of Pennsylvania, to Baltimore MD, to Washington DC and Richmond, VA. Not to mention the peninsula shared by Maryland and Delaware. It accesses the heart of America. Fortress Monroe was built right on a spur at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on the waters edge of a major shipping channel called Hampton Roads.

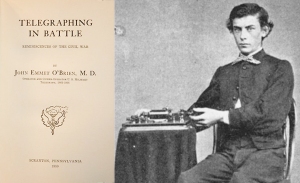

At the beginning of the Civil War the US military was in chaos. No one knew for certain what allegiance military personnel would favor. Most of these Third System forts in southern territory fell into the hands of the Confederacy. All in Virginia fell. Save one. Fort Monroe. As a result this made it the most important Union military installation during the Civil War. From here Federal troops could threaten Richmond itself as well as stage supplies and launch attacks down the coastline. It could also threaten Gosport Shipyard (now Norfolk Navy Yard) across the bay. Gosport/Norfolk was the maritime capitol of the United States and had fallen into the hands of the Confederacy. At the outset of the war Fort Monroe was considered the front lines and it was under these circumstances that Richard and John arrived.

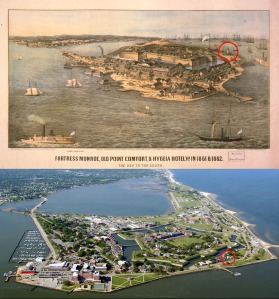

The pictures above show how the fort looked in 1860 and how it looks now. At the time the Hygia Hotel, featured prominently in the foreground of the print, was a high end spa and get away. Unfortunately, it no longer exists. The island also features a lighthouse that still stands (I have placed a red circle around it to indicate its orientation). The fort housed the School of Artillery and was still active until it’s decommission by President Obama in 2011. It is now considered a National Monument and park with a historical museum. This is were Cindi Verser and I planned to meet.