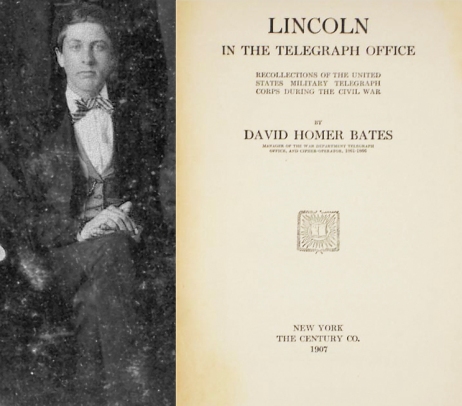

My first major find was a book by David Homer Bates called “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office”. Along with my great great grandfather Bates was another of the “4 Immortals” and published this book in 1907.

My first major find was a book by David Homer Bates called “Lincoln in the Telegraph Office”. Along with my great great grandfather Bates was another of the “4 Immortals” and published this book in 1907.

When these 4 men answered the call to war they were first stationed in key areas around Washington DC. Bates was assigned to the War Department and stayed in that post throughout the entire Civil War. He was quite possibly in the most unique position of any telegraph operator as President Lincoln spent many hours in Bates’ office sending and receiving messages. Besides getting to know the President personally, Bates tells of Lincoln writing much of the Emancipation Proclamation in the telegraph office of the War Dept.

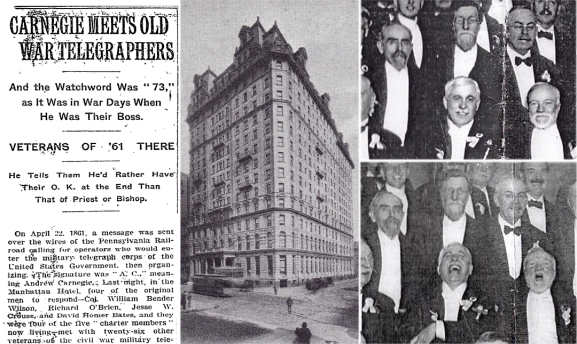

As for my family history Bates mentions Richard O’Brien on multiple occasions, along with Richard’s younger brother John Emmet. From these citations I learned that John was also active as an operator in the Civil War and that they were both stationed at Fort Monroe in Virginia. John Emmet is 13 when enters the service.

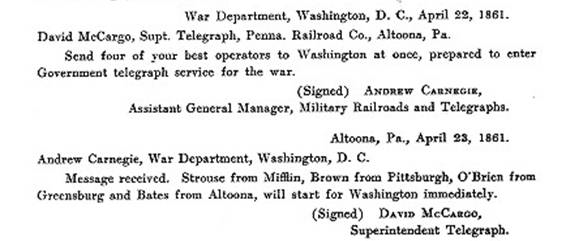

A few other names come up in this book that prove to play a role further down the line like Thomas Eckert, William Plum and Anson Stager. It is from this book I learn that the Unitest States Military Telegraph Corps remained a civilian organization throughout the war and was funded for the first seven months of the conflict out of the pocket of the Pennsylvania Rail Road.